[ad_1]

“Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” — Benjamin Franklin, in a letter to Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, 1789.

Thankfully, after more than a year with innumerable challenges, it appears that the pandemic will end. From an economic perspective, the government acted boldly to support households and businesses through the crisis with monetary and fiscal stimulus. Now, just as the recovery has commenced, after a four-year pause we are at the beginnings of another tax debate.

In this column, my aim is to provide you with some of the context for this debate with respect to the state of the U.S. federal budget, particularly on the revenue side, and of overviews of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and President Biden’s tax plans and the two 2021 proposals: The American Jobs Plan and The American Families Plan.

Government budget and tax statistics

For those looking to quickly understand the current state of the U.S. federal budget, I would recommend looking at the new set of infographics put together by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). As shown there, in fiscal year 2020, the federal government spent $6.6 trillion, while it took in $3.4 trillion in revenue. I expect I will be writing more about the implications of budget deficits that exceed $3 trillion in future columns, but today I wanted to focus on the revenue side.

In FY 2020, the infographic shows that of those $3.4 trillion in revenues, individual income taxes accounted for $1.61 trillion, payroll taxes for $1.31 trillion, corporate taxes for $212 billion, and other revenues for $289 billion. Other revenues include remittances from the Federal Reserve ($82 billion), excise taxes ($87 billion), customs duties ($69 billion), estate and gift taxes ($18 billion), and miscellaneous fees and fines ($35 billion).

I highlight these data both because it is interesting to see the relative magnitudes of these different revenue sources, and because it might surprise some people, given the amount of ink spilled on some of the smaller items.

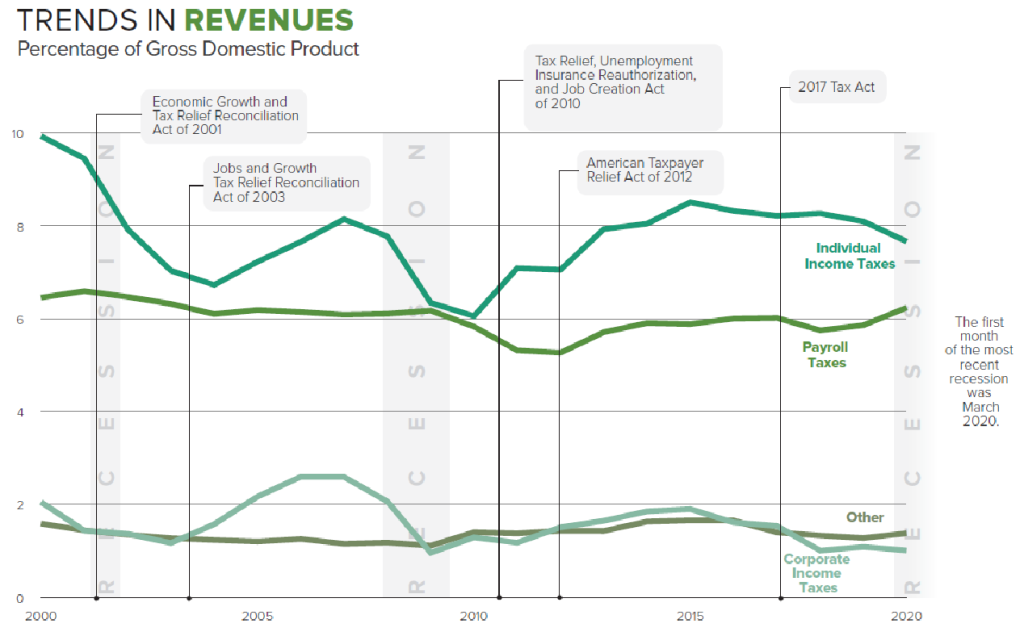

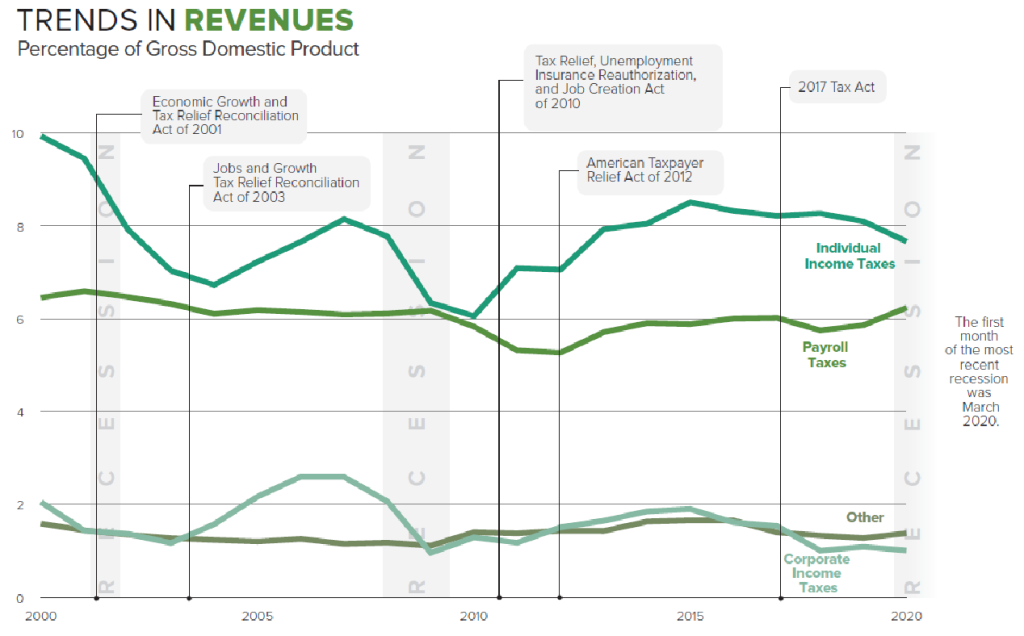

Next, it is worth looking at how tax revenues have changed over time. In Exhibit 1, revenues are measured here by the CBO as a share of GDP. The economy grows over time, and revenues on a dollar basis grow with it. Measuring these revenues as a share of GDP scales them appropriately. Tax revenues tend to increase when the economy is booming and fall during recessions.

In addition to these changes, the different revenue components can rise or fall if tax policy changes. The major tax bills, including the TJCA, are shown in this chart. These four types of revenues are ranked the same as they are in dollar terms; and in total, revenues were 16.3% of GDP in FY 2020. On average, that share has been 16.8% over the last 20 years. In FY 2020, both individual and corporate taxes declined as a share of GDP due to the recession.

Goals of tax reforms

Understanding some of the top-line numbers with respect to the federal government’s revenues, let’s review the TJCA and discuss the changes that Biden’s tax plans are proposing. It is helpful to begin by thinking about what each proposal aimed to accomplish.

At the highest level, tax reforms can be placed in one of three categories: tax increases, tax cuts, or revenue-neutral “fundamental” tax reforms. The goals of the first two are straightforward – to raise more revenue to address rising deficits or offset additional spending, in the first case, or to boost the economy by cutting taxes, in the second. A fundamental tax reform attempts to improve the efficiency with which taxes are collected to improve the economy’s functioning.

Clearly, actual proposals can be combinations of these categories and the labels can sometimes be in the eye of the beholder. For the two proposals discussed here, the TCJA was a fundamental tax reform/tax cut with a goal to increase the rate of growth, while the Biden administration proposals overall represent a tax increase motivated to support increased spending.

To its proponents, the TCJA was a fundamental tax reform with goals to lower marginal tax rates and broaden the tax base by eliminating deductions and exemptions. There were also efforts to simplify the tax code by doubling the standard deduction, which greatly reduced the number of households that needed to itemize deductions.

Proponents forecast that this type of tax reform would make U.S. corporations more competitive, would increase productivity and economic growth, and as a result, would lead to a revenue neutral outcome – even though households and businesses would be paying at lower marginal rates.

Those opposed to these changes argued that the cut in marginal rates for corporations and individuals would lead to a disproportionate tax break for those with higher incomes. That concern highlights another common goal of tax reforms, i.e., to alter the distribution of taxes paid.

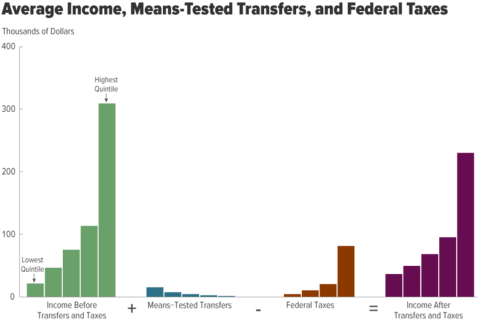

Again, it is helpful to look at the data on this question. Exhibit 2 below shows the income before taxes, means-tested transfers, income taxes, and after-tax income by household income quintile. A few items to note:

- The highest income group has much higher average income on both a pre-tax and after-tax basis. This group also pays a large share of federal taxes. (Looking within this highest 20% of earners, this pattern is also true when you look at the top 1% or top 0.1%. The tax code is progressive, with higher earners paying at a higher rate).

- The middle three quintiles pay a smaller share of federal taxes, but don’t receive much in the way of means-tested transfers. As a result, their level and share of after-tax income is similar to that for their pre-tax income.

- The lowest 20% of earners receive most of the means-tested transfers and pay no federal income taxes. (They do pay payroll taxes). The combination means that after-tax income is higher than pre-tax income for this group.

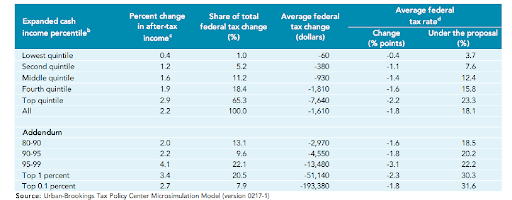

The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) is one of the groups that produces detailed analyses regarding the distributional impacts of tax proposals. As shown in Exhibit 3, the TCJA was anticipated to lower taxes across the income distribution, but the average tax cut in dollars and percentage points was larger at the top of the distribution. Note that the TPC analysis provides additional detail at the high end of the distribution.

Distributional Impact of the 2017 TCJA

The TCJA made a number of changes to the tax code. Among those of most interest to mortgage market participants were provisions that:

- Lowered corporate rates from 35% to 21%, but limited some corporate deductions

- Lowered individual income tax rates at all levels except the lowest income bracket

- Doubled the standard deduction but limited or eliminated exemptions and other deductions, including:

- Limited deductions for state and local taxes (SALT) to $10,000; and

- Reduced the cap on the mortgage interest deduction (MID) from $1 million to $750,000

- Added a deduction for pass-through businesses (199a) where up to 20% of Qualified Business Income (QBI) could be deducted.

- The changes to the corporate tax rate were “permanent,” while the changes to the individual provisions were limited to 10 years and are scheduled to snap back to their prior levels in 2026.

An industry concern during the debate on the bill related to a provision which would have eliminated the tax deferral on the creation of mortgage servicing rights (MSRs). MSRs are booked as a balance sheet asset when loans are sold into the secondary market and show as book earnings at that time. However, if the servicing is retained, the lender does not receive any cash income when the MSR is created. The tax deferral in the current code recognizes this difference between book and tax income, taxing servicing income over time as the cash arrives.

The TCJA included an exemption for MSRs to recognize this important aspect of lenders’ businesses. If this had not been included, it likely would have caused a sharp reduction in the value of MSRs, which would have both hampered liquidity in the MSR market, and ultimately would have been reflected in higher mortgage rates to borrowers, as the value of servicing is tightly connected to primary mortgage rates. As noted below, this concern has resurfaced again with the latest proposals from the new Administration.

The Biden administration proposals

The Biden administration has proposed the $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan (AJP) and the $1.8 trillion American Families Plan (AFP) to rebuild infrastructure, as well as provide new spending for a host of educational, public health, and other initiatives. To pay for these expenditures – at least partially, the plans include a series of provisions that would largely reverse the TCJA’s tax rate cuts for corporations and higher income individuals. As of this writing, I am basing my comments on the high-level summaries of the Biden tax plans provided. More detailed language is likely to be provided shortly.

I will focus here on the tax elements of the two proposals that would directly affect real estate markets. The real estate-related tax proposals fall into six main categories:

- The most significant “pay-for” in The American Jobs Plan (AJP) is an increase in the corporate tax rate from 21% to 28%. The plan also proposes a “minimum book tax” for corporations of 15%.

- The AFP would increase the top individual tax rate from 37 to 39.6%, reversing the cut from the TCJA.

- For households making more than $1 million, the AFP proposes an increase in the capital gains rate to 39.6%, putting it on par with the proposed top tax rate for ordinary income. Adding in the Medicare tax on investment earnings, the top capital gains rate would increase to 43.4%. The proposal would also eliminate the stepped-up basis of assets at death, increasing the taxation of intergenerational businesses.

- In addition to the changes to capital gains taxation, the proposal also recommends eliminating carried interest, a tax treatment that permits asset managers to recognize earnings from investments they manage as capital gains rather than as ordinary income. The 1031 like-kind exchange deferral of capital gains taxation would also be eliminated for gains greater than $500,000.

- No changes were proposed for the capital gains exclusion on primary residences. There was also no mention of changes to individual provisions (including the lowered MID cap and the SALT limitation) from the TCJA that will sunset after 2025.

- As part of the AJP, the administration is proposing to invest $213 billion in affordable housing. The expectation is that this would take the form of an expansion and revision to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), and perhaps the creation of a new Middle-Income Housing Tax Credit (MIHTC), as well as the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act (NHIA).

While each of these items have potentially important impacts on the housing and mortgage markets, I am going to focus on just a few. First, the minimum book tax has the same potential to disrupt the MSR market as the proposal in 2017. If lenders are taxed on the book gain from the creation of an MSR, well before they see the cash income from the servicing asset, servicers will retain less and sell more MSRs, putting downward pressure on MSR values. This market impact would be true even if the minimum book tax were only applied to the largest lenders, as a reduction in MSR values would be felt by all lenders in the market. Moreover, as noted above, a reduction in MSR values will ultimately lead to higher mortgage rates for borrowers.

With respect to the commercial real estate market, the limitation on 1031 like-kind exchanges, particularly in the context of potential increases in capital gains rates and an elimination of the step-up basis, will also have a depressing effect on the market. Investors in commercial estate utilize this provision to rollover capital gains from one property to a “like-kind” property. Given the long-term and unique capital demands of real estate, in the TCJA, this provision was retained for real estate investments, but the AFP would limit this treatment to gains under $500,000, which could curtail the pace of commercial real estate transactions and associated lending activity.

Although residents of states with high property values and steep state and local tax rates (e.g., New York, New Jersey, California) had been hoping for a reversal of the SALT deduction limitation, to date such a change is not part of the proposal.

What comes next

We are soon expecting more detailed versions of these proposals from the Biden administration. By mid-summer, Congress may be well on the way towards legislating on these topics. As always, the details of each of this tax provisions really matter, and they may change at any step along the way, from the administration’s initial proposal, to a final bill signed by President Biden.

Industry participants should keep a close eye on these proceedings, understanding the broader context of the debate with respect to the budget, the level of revenues needed to finance government spending, the distribution of tax liabilities, and the specific provisions which may impact real estate market

The post What the Biden tax plans mean for the housing market appeared first on HousingWire.

[ad_2]

Source link